Eric Blair, the real name of the pseudonymous George Orwell, died in 1950 at the age of 46 and since 70 years have passed since his death this means that publishers are free to publish anything that was in print before his death without having to pay royalties to his estate. Consequently, a new editions of all his works will be launched on the international book market in the months and years to come, so now is as good a time as any to ask what lies behind his enduring appeal and what are the best bits?

His complete works, the Collected George Orwell, adds up to 20 volumes – this includes all his novels, his journalism, which includes 700 book reviews, his diaries and some of his letters – 8,000 pages in all weighing 35 pounds and taking up two feet six inches of shelf space. No one but the dedicated completist would even attempt to read all this. Most readers know him for his two great novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four which, from the seventies onwards, have sold nearly a million copies a year in the US and UK.

These novels are as relevant now as they have ever been, not merely saying something about the failure of totalitarianism but expressing something fundamental about human nature itself. The words ‘doublethink’, ‘Thought Police’ and ‘Big Brother’ have become common currency in many languages throughout the world. The past few years have seen the regular appearance of articles in the media beginning with the entry point ‘If George Orwell Had Been Alive Today…’ to discuss topics such as Donald Trump, fake news and Brexit.

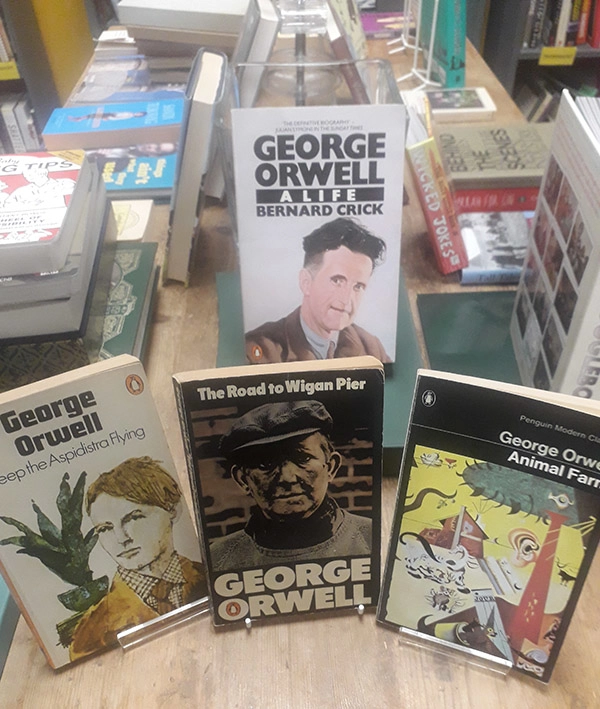

Readers wanting to experience a deeper understanding of Orwell should take a look at his two great masterpieces of social commentary, Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier. It is a key element of his greatness as a writer that much of what he wrote about came from personal experience: he was a policeman in Burma, a pauper in Paris and London; lived among unemployed workers in the North of England and army soldiers in Spain and he turned those hard won adventures into fables of imperialism, poverty and war. Everything he wrote has the feel of direct experience which is transformed, moulded into meaning, by his fierce moral sense.

The first book is a unique expose of poverty in the two great cities derived from Orwell’s experience at the end of the nineteen-twenties when he lived a state of near destitution and was employed as casual labour in various Paris restaurants. The second part of the book describes the life of various tramps he met in London. After the modest success of Down and Out, the publisher Victor Gollancz in 1936 commissioned Orwell to visit the industrial North to write about working-class conditions there.

In Lancashire and Yorkshire he met a different class of poor to the tramps and beggars of his previous book; The Road to Wigan Pier is about workers, men and women who wanted to work, but had no jobs. He portrayed the people he met as possessing the qualities of pride, dignity, generosity, strength and class solidarity. The book is both a celebration of their virtues as well as an angry polemic against their sufferings. It is a deeply moving work, written from the heart and one of his greatest achievements.

Another of his successes as a writer was to promote the idea of ‘plain English’ which he linked, both logically and emotionally, to honesty and truth-telling. In the thirties it was current among many prominent English writers to suggest that there is a direct correspondence between plain English and plain decency: those with an elaborate style, it is implied, have something to hide (the sort of statement with which Donald Trump might concur). Today we might argue that a plain style is no guarantee of decency in morality and politics: a plain style is just a rhetorical construction like any other and can just as easily be the vehicle for lies as for truth.

Orwell wrote four important essays on the English language which are still available to buy as pamphlets: ‘The Prevention of Literature’; Writers and Leviathan’; Politics v. Literature’; and Politics and the English Language’. He had a hatred of cliché and all kinds of clumsiness of expression and he had the conviction that clarity of language was necessary to clear thinking and that clear thinking was essential to social health. His essay ‘Why I Write’ is still required reading for all would-be writers.

He seems not to have been an easy man to get to know and the relationship between his writing and his life was complex: nearly all of his work is deeply autobiographical. On his deathbed he made his wife promise that there would be no authorised biography; nevertheless Sonia Orwell gave some permissions for material to be quoted in George Orwell: A Life by Bernard Crick. Other books have followed; the best so far has been Orwell: A Life by D.J. Taylor, a work of great insight and imaginative empathy which won the Whitbread Prize in 2003. A host of new biographies and a film of his life are scheduled for this year which is encouraging news for anyone wanting to learn more about this remarkable man.

By Mark Jackson-Hancock, book expert, Chapter Two

Share Article